Is it Operant Conditioning or Positive Reinforcement Training?

Balinda Strosnider, CPBT-KA

Land On Sky Wildlife Experiences

As a long-time trainer of birds of prey, I was taught to use a more traditional method of training. In recent years, I have changed my thinking and my methods to a more modern approach. However, I have always struggled with what to call this modern method of training that is being used to train our avian earth-mates or frankly any animal. I hear the terms “Operant Conditioning” and “Positive Reinforcement” used interchangeably to describe the non-traditional method of training. While these terms are correct at least in part, they don’t describe the fundamental difference between the two methods of training.

First, let me clarify the difference between Operant Conditioning and Classical Conditioning.

In Psychology, Operant Conditioning is learning behaviors from consequences. Consequences associated with a behavior will adjust our behavior in the future. For example, if you put your hand on a hot stove (behavior) and you get burned (consequence), chances are that you will not put your hand on a hot stove in the future. Conversely, if you used your (non-burned) hand to press a button and piece of chocolate fell out of the sky, you would probably repeat that behavior of pressing the button. At least I would.

Classical Conditioning deals with learning by association. When we have a conditioned response such as feeling hungry when we smell our favorite food, we can change the original stimulus (smelling favorite food) to be something else completely unassociated by pairing it with the original stimulus. The famous Pavlov experiment is an example of classical conditioning. When his dogs saw food, they would salivate. This is a natural and unlearned response. Pavlov paired showing his dogs food with the ringing of a bell. Eventually the dogs would start to salivate just by hearing the bell. Transferring the stimulus of seeing food to the ringing of a bell for the same response (behavior) is Classical Conditioning.

In both the traditional and modern methods of training, we can use both Operant Conditioning and Classical Conditioning methods. For example, my owl Funky has learned to fly to his crate (behavior) when his door opens (antecedent) because every time he goes into his crate (behavior), he is rewarded with a nice portion of food (consequence). Funky likes his food, so when I ask him to crate again, he is willing to do so (Operant Conditioning). Using positive reinforcement, he has been ‘conditioned’ to fly to his crate when he hears the crate door open. I have also paired opening his crate door with a whistle. He has made that association and now when he hears the whistle blow, he flies into his crate. This is Classical Conditioning and is appropriate to use in both the traditional and modern methods of training. So “Operant Conditioning” is technically not the correct term for the modern method of training.

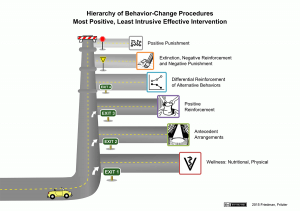

Since the tools and techniques that trainers use can be vastly different between the two methods, can we use the term “Positive Reinforcement Training” instead? Susan Friedman (BehaviorWorks.Org) and James Fritzler developed the Humane Hierarchy to explain the continuum of reinforcing and punishing behavior. See Figure 1.

Figure 1- Humane Hierarchy

The purpose of the humane hierarchy is to exhaust all of the tools at the lower levels first before utilizing methods/tools in the upper tier caution zones. Reinforcement methods are seen more on the lower tiers while punishment methods are seen at the higher tiers. Many people call this thought process “positive reinforcement training” and I would agree that is a pretty fair assessment of the modern training method. The modern training method tends to focus on the lower rungs of the hierarchy and the traditional training method tends to focus on the upper rungs of the hierarchy by using more punishing or domination-style training methods.

However, using the term “positive reinforcement” still does not capture the full fundamental difference between the two training methods. You can still go in and grab jesses of a bird so they have no choice to leave and then feed them on the glove for being good, thinking that you are offering positive reinforcement. The problem is, in order to determine if a reward is an enforcer, the animal has to be able to choose to do that behavior again. When you remove their choice long enough (always grabbing jesses and forcing to sit on the glove), many of them give up making any choice in a condition called Learned Helplessness. Seligman demonstrated this in his experiments where dogs were put in a crate with a low voltage charge to their feet. The dogs would try to get out of their box, but eventually realized they could not and would give up the fight. They gave up to the point that when the box was eventually opened, they still did not try to leave. Learned Helplessness has been replicated with a wide variety of animal species such as dogs, cats, monkeys, cockroaches, children, and adult humans. (Friedman, 2020). This methodology is certainly not the intent when someone describes their training method as “Positive Reinforcement” training nor is it the intent of the modern training method. Thus, we need to look deeper to the more fundamental differences.

The fundamental difference is even further entrenched in the mentality of the training. Indeed, the fundamental difference is the amount of choice the animal is given. From the very beginning of training, the animal needs to have choice and control. Using traditional restraining methods to “break” the animal first and then building a relationship using positive reinforcement does not align with “Choice-based” training. This is ultimately the term I was looking for.

It boils down to choice-based training (new method) vs. dominance or restraint training (traditional method) and indeed, both methods work. But the difference in attitude and well-being of the animal is generally visible. Animals trained using dominance theory or punishing methods tend to exhibit more aggression, anxiety, and escape behavior. (Martin, 2020) And when escape behavior is repeatedly

blocked, learned helplessness can follow (Overmier & Seligman, 1967). Choice-based training using the most positive methods possible promotes voluntary cooperation with the animal, reduces stress, avoidance behavior and aggression, and is clearly the way of the future. Following in the footsteps of older professions such as mental health, special education, medicine, bioethics, and law, animal oversight organizations such as AZA and other professional organizations (e.g., IAATE, IAACB, and APDT) are incorporating more of these methods into their standards. We have a wide range of tools for training at our disposal, but from an ethical perspective, “effectiveness is not enough” (Friedman, 2020). “Choice” has been shown to be a biological need for behavior health (Friedman, 2014). We owe it to the animals in our care to provide them with at least their basic needs which includes control. Choice-based training IS the preferred ethical training method. And while the standards may change as we continue to learn and refine our training methods, we will not go backwards to the more traditional, coercive methods.

REFERENCES

Martin, S. (2020, August) Improving Animal Welfare Through Training https://naturalencounters.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Improving-Animal-Welfare-Through-Training.pdf

Freidman, S. (2014) From parrots to pigs to pythons: Universal principles and procedures of learning. In: Tynes VV, ed. The Behavior of Exotic Pets. Blackwell Publishing, in press.

Freidman, S. (2020) Why Animals Need Trainers Who Adhere to the Least Intrusive Principle: Improving Animal Welfare and Honing Trainers’ Skills. http://www.behaviorworks.org/files/articles/Why%20Animals%20Need%20Trainers%20Who%20Adhere%20to%20a%20Procedural%20Hierarchy.pdf

Overmier, J. B., & Seligman, M. E. (1967). Effects of inescapable shock upon subsequent escape and avoidance responding. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 63(1), 28–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0024166