The History of Animal/Bird Training

Balinda Strosnider, CPBT-KA

Land On Sky Wildlife Experiences

The journey to choice-based training methods

Evidence of domesticated animals dates back to over 30,000 years ago. While we are unsure about the training of the animals, “the earliest evidence of the dog collar in Egypt is a wall painting dated c. 3500 BCE of a man walking his dog on a leash.” (Mark, 2019) Certainly some form of rudimentary training was conducted to enable a dog to at least walk alongside its human. While animal training may have been taking place thousands of years ago, there is not much documentation on the subject until WWI.

Currently, there are generally two camps to animal training. The traditional method is steeped in dominance theory based on observations of animals in captivity. Modern training methods stem from behavioral psychology. While both methods sprouted roots around the same era, the traditional approach took off shortly after the turn of the century out of necessity. It is said that “necessity is the mother of invention” and the start of WWI brought about the need for rapid training methods.

While traditional training methods are still prevalent, the modern training method is quickly becoming the preferred animal training method. Modern training methods are based on scientific evidence with animal welfare in mind. The modern training method has been found to be useful on pretty much any animal, from fish to humans. And the ethics of this modern training is being embraced by animal oversight organizations such as the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) and other professional organizations (e.g., IAATE, IAACB, and APDT).

Traditional training methods

During the first world war, dogs were used to assist the service men in combat. As a result, the need arose for quick training methods to supply the front lines with a revolving door of canine assistance. The need for such rapid training brought about the era of Compulsion training headed up by Konrad Most. Compulsive trainers often use special collars like the choke collar or prong collars that dig into the animal’s neck. The compulsive training method is based on punishment and negative reinforcement. The punishment inflicted on the dog is aversive, and behavior compliance (sitting still or not pulling) is the only thing that will remove the discomfort or pain. Konrad and his methods were again utilized in WWII and more dog trainers were developed in the military. Post war, Konrad was joined by Willian Koehler who also trained military and police dogs. Koehler’s methods were even more brutal. He advocated methods that included “hanging and helicoptering a dog into submission (into unconsciousness, if necessary). For example, to stop a dog from digging, Koehler suggested filling the hole with water and submerging the dog’s head in the water-filed hole until he was nearly drowned.” (Miller, 2019) Luckily, when Konrad Most’s famous book about training dogs was reprinted in 2001, the publishers warned that some of the “compulsive inducements” … were unnecessarily harsh. (Most, 2001) The problem with compulsion training is that it can lead to fear and aggression behaviors in many animals.

Combine this compulsion training practice with the dominance theory based on a study of captive wolves conducted in the 1930s, and you get the dominance-based, traditional approach to training animals. The dominance study was conducted by animal behaviorist Rudolph Schenkel, in which the scientist concluded that wolves in a pack fight to gain dominance, and the winner is the alpha wolf.

The concept of the alpha wolf was further entrenched by wolf research scientist David Mech who wrote “The Wolf: Ecology and Behavior of an Endangered Species,” in 1968. At that time, the alpha theory was all that was known and was observed in wolves in captivity. But after studying wolves in the wild, Mech found that the dominance theory was incorrect. Leaders of packs became the leaders by breaking off and starting their own families, not by dominating their way to the top. His book is still in print despite his numerous pleas to the publisher to stop publishing it. (Mech, n.d.) Even though the alpha theory was based on wolves, it was easy to extrapolate the method to dogs since modern dogs are decedents of wolves.

Perhaps the most popular advocate of this inaccurate concept, Cesar Millan, is only the latest in a long line of dominance-based trainers who advocate forceful techniques such as the alpha roll. Much of this style of training has roots in the military – which explains the emphasis on punishment. (Miller, 2019)

More specific to the bird world, the art of falconry has its own traditional methods. Two popular techniques used are “manning” and “waking”. While most articles I read about falconry frowned upon domination of birds of prey, manning and waking are arguably domination methods. In both cases, the animal is restrained and exposed to aversive stimuli; and in the case of waking, is also deprived of sleep. After discussing a more modern approach to training, it will be evident why these methods are not the best choice.

The beginnings of the psychology of learning

During the 1890s, Russian physiologist, Ivan Pavlov was researching salivation in dogs in response to the site of food. By pairing the presentation of the food with a bell, Pavlov was able to instigate the salivation process by simply ringing the bell. This association to a new stimulus is known as Classical Conditioning and is considered to be the first basic law of learning.

Around the same time (1898), Edward Thorndike developed the law of effect principle which suggests that behaviors that produce a satisfying effect are more likely to occur in the future and that behaviors that produce a discomforting effect are less likely to occur again in that same situation.

Burrhus Frederic Skinner, better known as BF Skinner, based his work on Thorndike’s law of effect. Skinner took Thorndike’s premise and used it as a foundation of how animals learn. In order to explain his theory of operant conditioning, Skinner introduced the terms “Reinforcement” and “Punishment” which align to Thorndike’s idea of behaviors happening more or less often respectively. He also coined the terms “Positive” and “Negative” and you can read more about them in the Operant Conditioning Terminology blog.

The work of Skinner was rooted in a view that classical conditioning was far too simplistic to be a complete explanation of complex human behavior. He believed that the best way to understand behavior is to look at the causes of an action and its consequences. He called this approach operant conditioning. (McCloud, 2018, January 21) Through operant conditioning, an individual makes an association between a particular behavior and a consequence (Skinner, 1938).

Enter Sidney Bijou (1968) with an attempt to better data gathering techniques. When measuring a behavior scenario, he found it was easier to break down the situation into 3 parts: antecedent, behavior, consequence. Antecedent = the situation or environment that can trigger a behavior. Behavior = the behavior that occurs after the antecedent situation. C = the consequence that ensues immediately after the behavior.

Building on the works of Thorndike’s (law of effect principle), BF Skinner (Operant Conditioning), and Bijou (Antecedent, Behavior, Consequence), Operant Conditioning became the gold standard in professions such as mental health, special education, medicine, bioethics, and law.

The rise of ethical training methods

Even though Operant Conditioning techniques were first studied in the 1800s, the practice of using the methods did not start taking root until nearly a century and a half later.

The movement towards gentler training methods began with two of Skinner’s students, Keller & Marian Breland. The Brelands, began applying operant conditioning as a practical training method in 1943. They made their own clickers and trained many animals, from cockroaches to parakeets to dogs. By 1948, they had a growing business. Within ten years, they had spread the use of applied operant conditioning to cats, dolphins, parrots, sheep, cattle, raccoons, and dozens of other species. (Bailey, 2002)

Although the Brelands promoted “clicker training”, the technique was not popularized until Karen Pryor published Don’t Shoot the Dog in 1984. Pryor and her cohort, Gary Wilkes started wide-spread clicker training classes in the early 90’s and have trained thousands in the positive reinforcement methods.

Shifting training to the birds

Dr. Susan Friedman is a psychology professor at Utah State University who pioneered the application of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) to captive and companion animals. While her training and methods are based on applied animal behavior and are useful for all animals, Susan is widely known in the parrot and avian circles. Professional organizations such as the International Association of Avian Trainers and Educators (IAATE) and the International Association of Animal Behavior Consultants (IAABC) promote her efforts in the professional avian and animal communities.

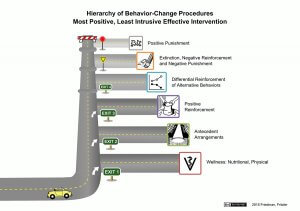

Dr. Friedman is credited with developing the human hierarchy in an effort to prioritize the tools in our training toolbox. See Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Humane Hierarchy

The purpose of the humane hierarchy is to exhaust all of the tools at the lower levels first before utilizing methods/tools in the upper tier caution zones. It promotes positive reinforcement methods and the concept of choice as a primary reinforcer over negative methods or methods of punishment. Note that the psychology terms “negative” and “punishment” have a different definition than what we are used to in the vernacular. For a definition of these terms, see this post. If you have not familiarized yourself with the psychology definitions of these terms, you will have to just trust me on the next paragraph.

Let’s revisit the falconry methods of manning and waking. When the bird is restrained by jesses, the falconer is relying on the effects of negative reinforcement. As the bird bates it is restrained by the jesses; the consequences of hanging upside down and the pressure on the legs (negative reinforcement) increases the likelihood of sitting on the glove. (Dillon, 2012) The idea is that the bird will quickly become ‘habituated’ and the relationship building can begin. However, these methods are a type of “flooding” that can lead to “learned helplessness”. Some birds of prey will be resilient, but many will exhibit unwanted behaviors (such as aggression or avoidance behavior) and the blame will be placed on the bird (ex: This hawk is just ‘mean’ or being a ‘bitch’ or ‘difficult’). One of the first principles you learn in choice-based training is that it is NEVER the animal’s fault. Trainers with decades of experience agree. Aggression leads to aggression…and aggression is the first resource of the incompetent. (Minette)

For more information on the behavioral psychology of animal training and why modern methods are more ethical, see my blog post.

Summary

Traditional training methods were born out of necessity and what we understood at the time. We have learned so much about how to improve our training methods, both from an ethical perspective and a behavioral reliability perspective. We have come a long way in combining animal behavior science with animal training. It has been a long and uphill road, but progress is being made.

I have heard people who continue to cling to the old methods indicate that standards will change again anyway, and I couldn’t agree more. However, we will not go backwards in our endeavors. It would be like doctors who used to participate in blood-letting practices waiting around and refusing to move forward in the hopes that those archaic practices somehow come back into fashion. As Maya Angelou said, “I did then what I knew how to do. Now that I know better, I do better“. Let’s not beat ourselves up (or others) over using methods that are outdated and perhaps a bit questionable, but rather let’s continue to strive to improve them.

Personally, I am excited about the future of animal training…a future where humans are more humane to their animal counterparts and learn how to communicate and build relationships.

References

Bailey, R. (2002). Click for Joy! clickertraining.com. Foreword and Introduction. Retrieved on December 08, 2020.

Dillon (2012, April 14). North American Falconers Exchange. Thoughts on Manning, from a Behaviorism Perspective. http://www.nafex.net/showthread.php?14399-Thoughts-on-Manning-from-a-Behaviorism-Perspective

McLeod, S. A. (2018, January, 21). Skinner – operant conditioning. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/operant-conditioning.html

Mark, Joshua J. (2019, January 14) Dogs in the Ancient World. Ancient History Encyclopedia (online). https://www.ancient.eu/article/184/dogs-in-the-ancient-world/

Mech (n.d.). Retrieved on December 22, 2021 from https://davemech.org/wolf-news-and-information/

Miller, Pat (2019, June 21) Debunking the “Alpha Dog” Theory. WholeDog Journal. Retrieved January 05, 2021 from https://www.whole-dog-journal.com/behavior/debunking-the-alpha-dog-theory/

Minette (n.d.) Just Another Reason NOT to use Compulsion in Dog Training! [Blog post]. Retrieved on January 15, 2021 from https://thedogtrainingsecret.com/blog/reason-compulsion-dog-training/

Most, K. (1954). Training Dogs, (J. Cleugh, Trans.), New York: Dogwise Publishing, 2001.

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The Behaviour of organisms: An experimental analysis. New York: Appleton-Century.